Trish Roberts made her mark at Tennessee in just one season, setting nine records.

This is the first Inbox-and-One history lesson, with many more to come! I’m committed to telling the stories of the incredible woman who paved the way for the game we all love. Let’s learn about them together.

Six women’s basketball jerseys hang in the rafters at Tennessee: No. 22 Holly Warlick, No. 30 Bridgette Gordon, No. 32 Daedra Charles, No. 23 Chamique Holdsclaw, No. 24 Tamika Catchings and No. 3 Candace Parker.

All six players made history at Tennessee. But one player, whose legacy is perhaps the most impactful of everyone to come through the Lady Vol program doesn’t have her jersey in the rafters. Not because of importance, or skill, but simply because everything she did happened over just one season, making her ineligible.

Her name is Trish Roberts and retired jersey or not, she made her mark on Tennessee basketball history. Roberts was the first black woman to play for Pat Summitt.

She was the program’s first All-American.

She led the Lady Vols to their first Final Four.

She holds nine Tennessee records, including most points in a contest (51), a mark she reached in her debut game, most rebounds in a game (24) and most points in a single season (929).

And most importantly, Roberts created a path for every black player that played for Summitt for the next 35 years.

“She is a living legend,” Catchings said. “For me, being an African-American woman, she really paved the way and allowed us to have those opportunities.”

Trish Roberts competing for Team USA.

When she came to campus in 1976, breaking barriers was nothing new to Roberts. That’s because years earlier, when Roberts was heading into her freshman year of high school in Monroe, Georgia, she was part of the first group of students to experience integration in the school district.

It was a culture shock to say the least. Roberts’ five older siblings had all gone to the local black high school, and she grew up dreaming of the day when it was her turn to attend dances, like the Sweetheart Ball, participate in talent shows and celebrate her education at the Baccalaureate. Instead she had to go to a brand new school, located across town with no bus service to take her there. Roberts still remembers her first day of high school. She nervously approached the school’s front doors after enduring the exhausting walk across town, and scanned the posted list to find out what class she was in.

“The biggest thing I remember was that when I got to my classroom, all of the black kids were huddled on one side and all of the white kids were on the other,” she said. “The school had to do something about that, so from then on everything they did was by alphabetical order.”

But seating charts could only do so much to bring the students together.

“The thing that actually did it was sports,” Roberts said. “It started with the football team, because the year prior at the black school, they had won a state championship, so when they came over to the white school, people were excited.”

Roberts says she had a good time in high school. Her skills as a basketball player helped her fit in, but she didn’t limit herself. Roberts also ran track, played tennis and was even a member of the marching band where she played the B-flat clarinet.

Still, Roberts knew where her talent truly lied. And everyone else knew it, too.

“My brothers were always the best players on the team, so everyone looked forward to when a Roberts came through the school,” she said with pride. “So, everyone expected me to be good because I was tall, I was fast and I played with my brothers.”

Back then, girls in Georgia played three-on-three basketball with two players serving as “rovers.” That meant two players were always on defense, two on offense, and two others could play both. Roberts was a rover.

“That’s all I knew, because I had grown up watching my sisters play that way,” Roberts said.

She went on to win a state title, but Roberts graduated high school in 1973 — one year after Title IX went into effect, so she didn’t think college basketball was an option.

During her senior year, Roberts received a letter from the basketball coach at North Georgia College asking if she would be interested in trying out for the team. Roberts knew her parents wouldn’t be able to afford her schooling, so she tossed the letter to the side and tried to forget about it.

“In the back of my mind I thought it would be cool if I could go,” she said.

Instead, Roberts graduated from high school and went to work at the same uniform factory where her mother was employed. Together, they made work pants. Her mother was a presser and Roberts spent her days stitching the band on each pair of pants. Khaki, blue, gray, she remembers pair after pair coming her way. But the factory machines weren’t made for someone who was 6-foot-1. Her neck was constantly sore from leaning over the machine, and Roberts kept banging her knees.

After just two weeks, Roberts came home crying. She knew she couldn’t work at that factory any longer. The next day she visited her high school counselor — “Miss Morris,” she said. “I’ll never forget her name.”

Roberts showed Miss Morris her previously discarded letter from North Georgia College. Together, they sent in an application and found out Roberts qualified for financial aid. That, plus a work study program suddenly, made college basketball possible.

She played one season at North Georgia before following her coach, Linda Caruthers, to Emporia State College in Kansas. It was culture shock part two.

No grits for breakfast. No corn bread. No collard greens. No soul food of any kind. When Roberts started to feel homesick, it was obvious to Caruthers. So, she found a way to bring a little Georgia to Kansas.

“She went to one of the local restaurants and said, ‘Do you think you can make some grits? Trish is getting homesick,’” Roberts remembers with a laugh.

Years later, when Emporia inducted her into their hall of fame, Roberts made sure to give that restaurant a shout out.

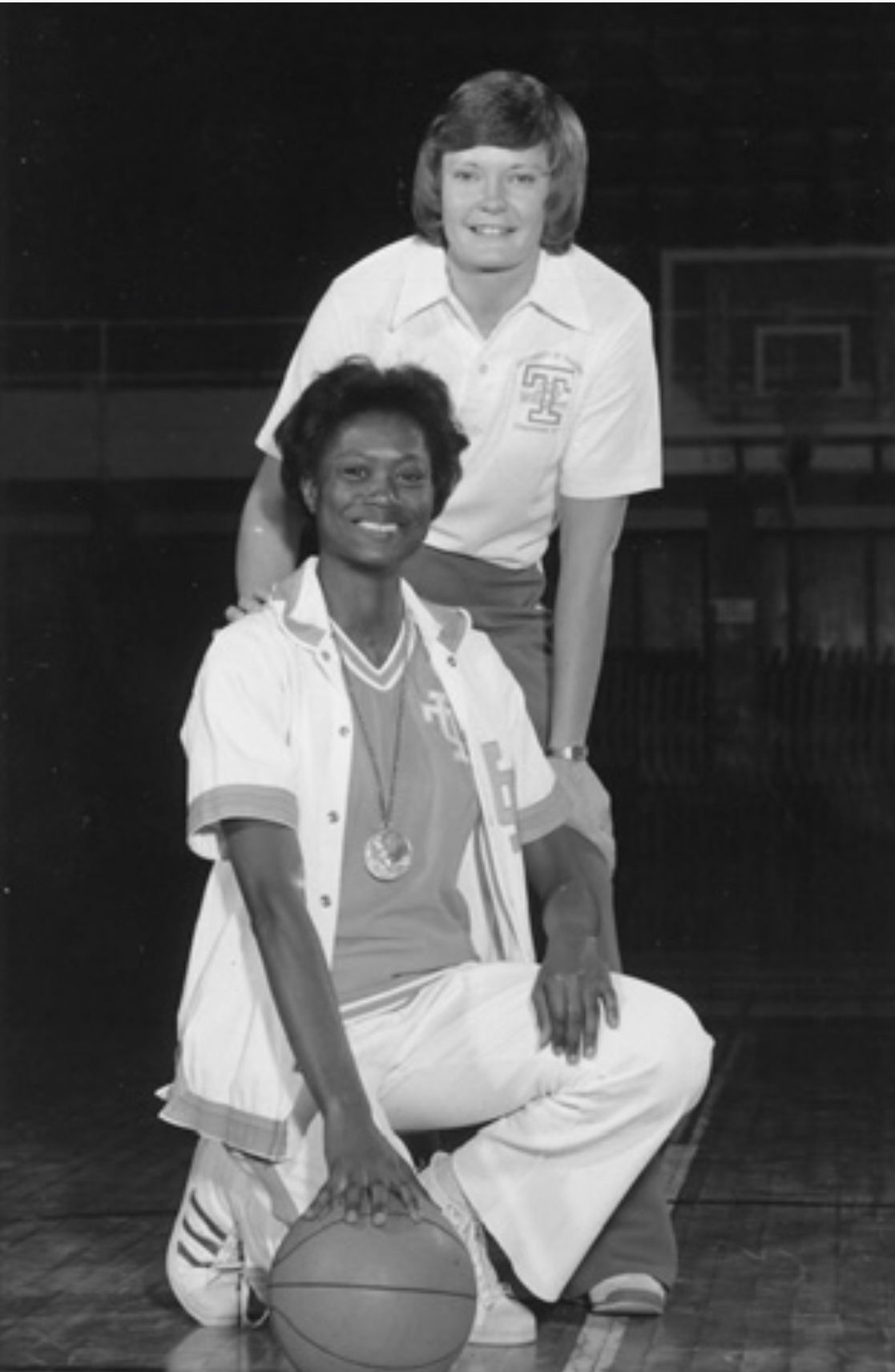

Trish Roberts and Pat Summitt as teammates on Team USA.

Caruthers did more than just make sure Roberts got her fix of soul food. She also helped Roberts get noticed, nationally. Playing for Caruthers was the beginning of a path that led Roberts to Tennessee, the Olympics and Pat Summit.

Roberts tried out for team USA twice — both times with Caruthers paying her expenses and traveling with her star player. The first time, Roberts didn’t make the roster. When she tried out the second time, Roberts was certain her fate would be the same. So convinced was Roberts, that before the last session of tryouts, she packed her bags and loaded them into Caruthers’ car. Roberts was ready to hit the road as soon as she left the court, but Caruthers convinced her to wait until the roster was posted.

“There was a crowd in front of the list,” Roberts said. “And girls were cussing, they were so mad if they didn’t make it.”

Roberts waited, nervously, until the crowd in front of the paper roster cleared. Then, she scanned it for her name.

“I saw my name and just started screaming,” Roberts said. “Then I ran downstairs and told my coach that I had made it. We had to bring my suitcases back upstairs.”

Just three years earlier, Roberts was slumped over a machine making work pants. Now, she was leaving the country to compete for Team USA in Montreal, Canada.

“I was a small-town girl,” she said. “I’d never even been to New York.”

Roberts experienced basketball euphoria on the Olympic team, as her squad earned a silver medal in the first ever women’s basketball Olympic competition. But in the midst of such a high, she found out that Caruthers had left Emporia. With just a few months until her senior season was set to begin, Roberts felt lost. She knew she couldn’t stay in Kansas without Caruthers.

Eventually, word got out to the team that Roberts wanted to transfer. One of her teammates was particularly interested in that information.

Pat Summitt was playing alongside Roberts on the Olympic team, but in the college scene, she was two years into her tenure as the head coach of the Tennessee Lady Vols.

“I had no idea that Pat was a coach,” Roberts said. “Becasue she was playing with me in the Olympics. But I still remember when she came up to me and asked if I would come play for her at Tennessee.”

Trish Roberts and Pat Summitt together at Tennessee.

Looking back, Roberts realized that Summitt was always there. Every photo of Roberts from that Olympics had Summitt in the background. On the bus, Roberts sat with her friend, Lusia Harris, but Summitt was always across the aisle or in the seat behind her. When the team went to Niagara Falls, there was Summitt, taking in the views next to Roberts. On the bench, Summitt was always in her ear, chatting about what was happening on the court.

“I realized she had been recruiting me that whole time without me knowing it,” Roberts said with a laugh.

Tennessee was much closer to home than Kansas, and Roberts was intrigued by the idea of playing for her teammate. What does your team look like? She asked Summitt.

The next day, Summitt brought Roberts a photo of her all white basketball team. Roberts showed it to Harris, who played her college ball at Delta State.

Can you imagine me in the back row of this picture? I’d be the only black player,

Trish, Harris responded matter-of-factly. I’m the only black player on my team.

It was settled. If Harris could do it then so could Roberts. That fall, she enrolled at Tennessee and came to campus site unseen. The Olympics closed on August 1, and Roberts was in Knoxville by the end of the month.

By the time she retired in 2012, Summitt had amassed a 1,098-208 record that included three AIAW Final Fours, and then, when women’s basketball became an NCAA sanctioned sport, 18 more Final Four appearances and eight national titles. Her immense legacy is wrapped up with that of Trish Roberts.

Pat Summitt and Trish Roberts at an awards ceremony.

Roberts helped Summitt to her first 20-win season. In her lone year at Tennessee, the Lady Vols went 28-5 and advanced to the program’s first Final Four, before losing to Harris and Delta State. Her numbers were outstanding. Roberts averaged 29.9 points and 14.5 points per game, while shooting 65 percent from the field. Versatility, which has become a fixture of the modern game, wasn’t common when Roberts was in college. Most people were either posts or they were guards. Roberts was both.

“I loved it when big, slow post players would try and guard me,” Roberts said with a laugh. “They’d come with me outside and I’d blow right by them.”

Her impressive numbers and unique skillset led Roberts to be Tennessee’s first All-American, an honor that players like Catchings would achieve decades later, following a path that Roberts paved.

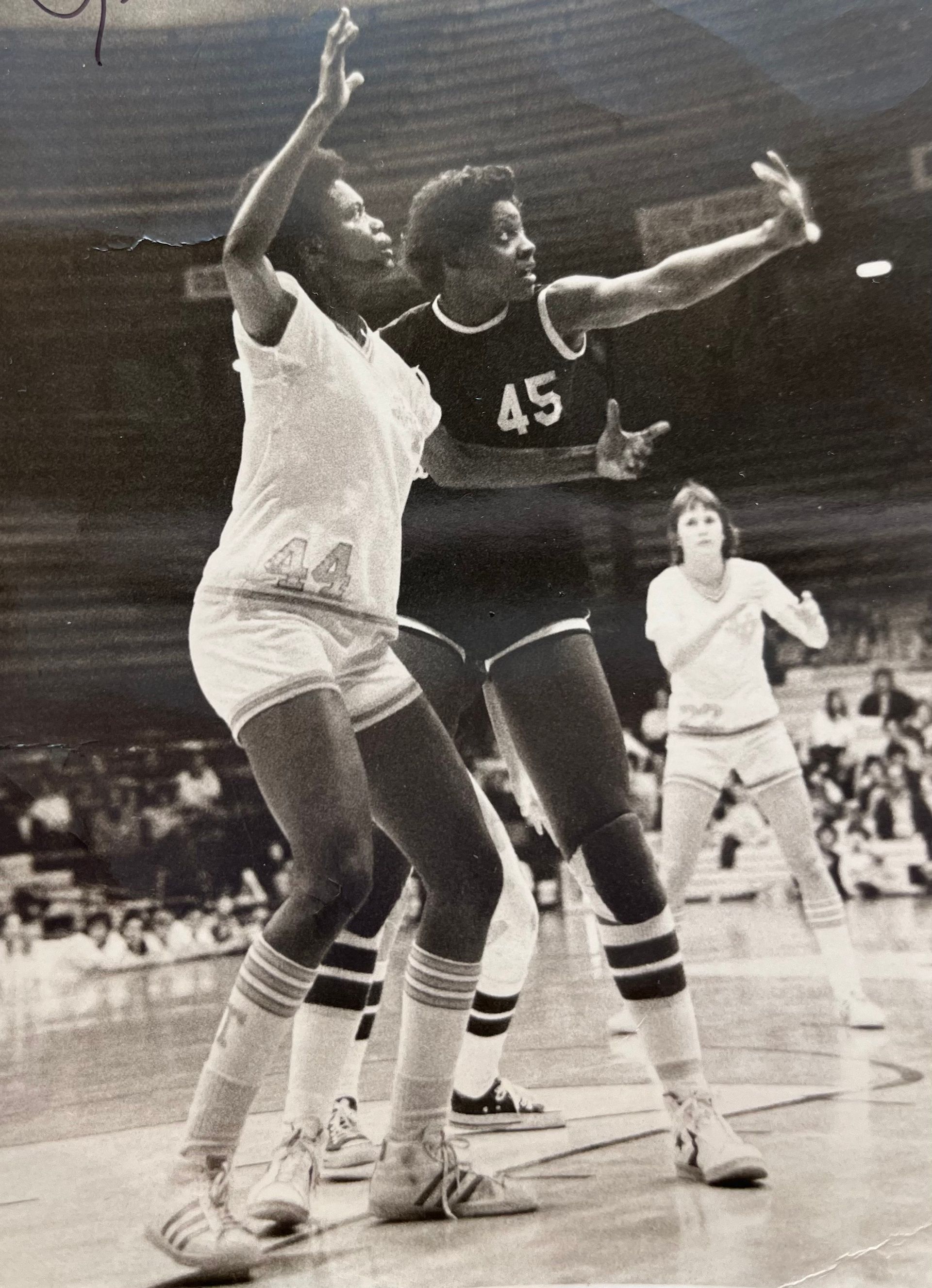

Trish Roberts, left, playing against Lusia Harris.

Tennessee wouldn't be Tennessee without Roberts. Someone had to be the first black player. The first All-American. The person who led Tennessee to its first Final Four.

But, despite all of her contributions, Roberts remains a victim of her times. AIAW players don’t get the recognition that NCAA players do. We saw that on a large scale when it took Caitlin Clark setting the all-time scoring record during her senior season for people to recognize that Lynette Woodard, a Kansas star and AIAW player, had held the record for decades, unnoticed.

If Roberts played today, or even 10 to 15 years ago, Catchings said, she would be revered as one of the greatest to ever play the game. She still should be.

“People would know all about her,” Catchings said. “She’d have all of the accolades she deserves. She would be all over the place.”

Trish Roberts put Tennessee on the map. Someone had to pave the way, and Roberts did it with aplomb and without complaint. Now it’s our job to give her the recognition she deserves.