This is a news and analysis article pertaining to ACL tears, an issue that has long impacted women’s basketball. Come back Thursday for the first Inbox-and-One history lesson, on Tennessee great Trish Roberts, who was the first black player for Pat Summitt and the first All-American in Lady Vol’s history.

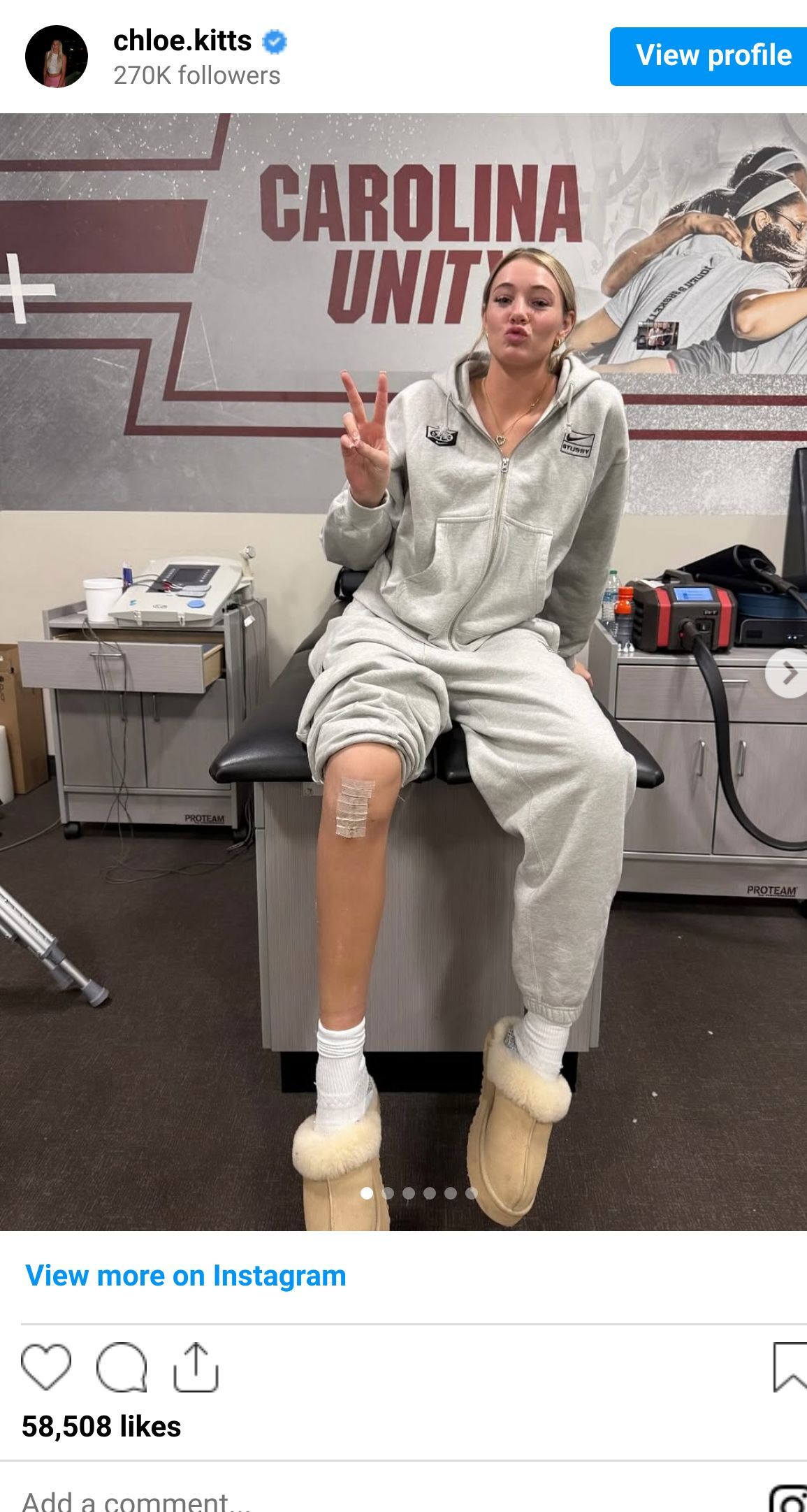

When college basketball started last week, reigning player of the year, JuJu Watkins didn’t take the court. Neither did South Carolina’s Chloe Kitts or Kentucky’s Dominika Paurová, who is out for the second season in a row.

All three suffered ACL injuries, something that’s common among women’s athletes. It’s one of the most devastating injuries a college basketball player can endure, given the recovery timeline. Between surgery and rehab, it takes at least a year, sometimes longer, to return to the court.

But most players do come back. The list of stars who have suffered ACL injuries and returned to exceptional college careers includes WNBA Rookie of the Year and former UConn player Paige Bueckers, tenacious Texas guard Rori Harmon, and TCU’s prolific passer Olivia Miles. Each of these players came back and played at the same level as before their injuries.

Years ago that wouldn’t have been possible, but advancements in ACL surgery, recovery and injury prevention have changed the game for these young athletes, salvaging their future professional careers.

“Return to sport is still not 100%,” said Dr. Micheal Medvecky, an orthopedic surgeon, professor and head team physician for the Connecticut Sun. “Most studies have it between 60-80%, but it used to be much lower.”

Major advancements have been made in the last 10 to 15 years, Medvecky says, particularly on the mental side.

“Your career depends on how well you do on the court,” Medvecky said. “So, there are additional stresses that happen. Not only worrying about reinjury, but just being able to play at a certain level. How do you perform at that level of stress? That can now be manipulated or improved based upon psychological training.”

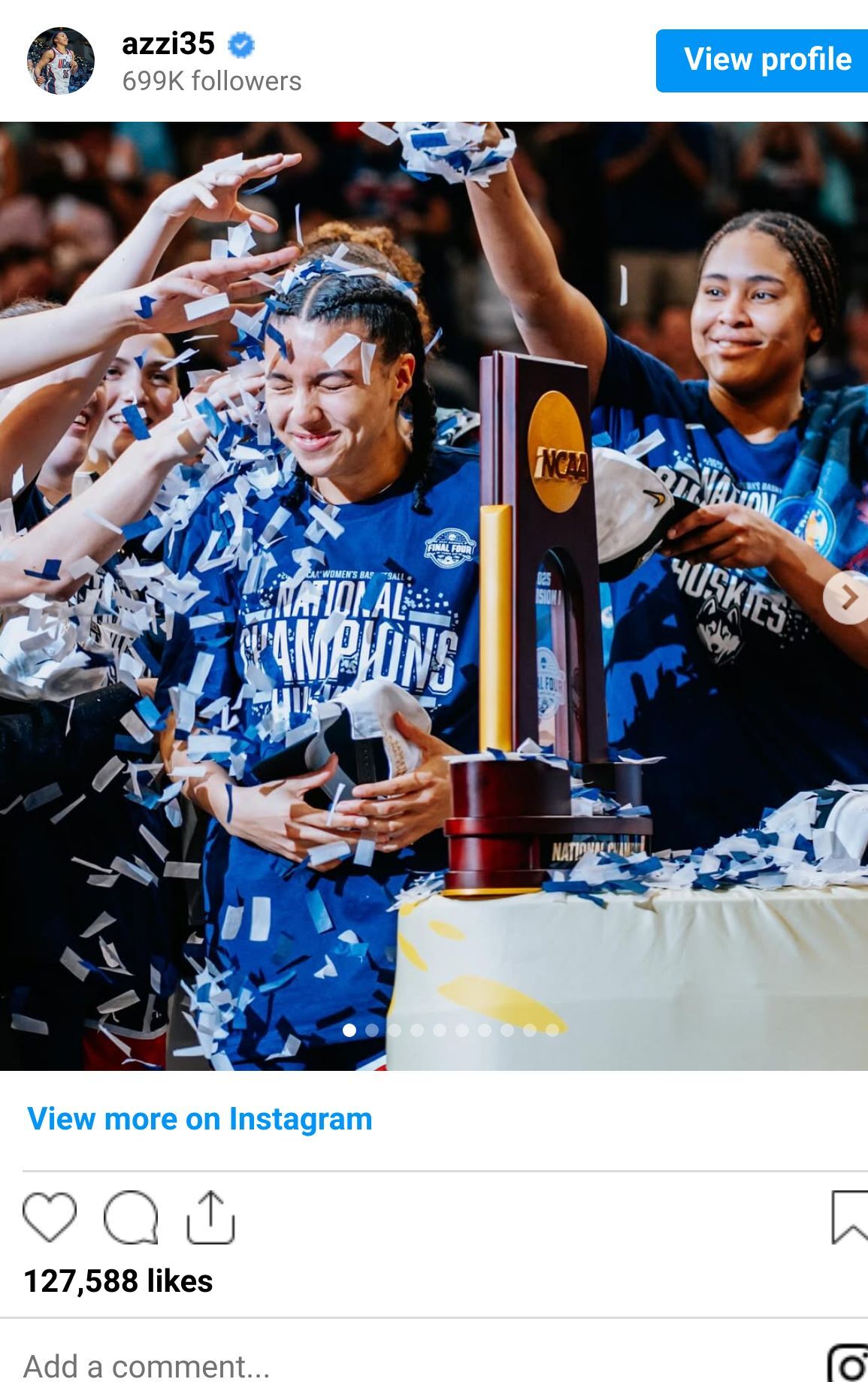

Players who come back from an ACL tear often have mental doubts and concerns about trusting their bodies when they return to the court. This is something UConn senior Azzi Fudd, who has endured multiple ACL tears dating back to high school, recently spoke about in a profile for ESPN.

Fudd said she didn’t “trust” her knee or her recovery. She went on to say that she wondered what she was even doing on the court. Fudd ended up working her way back, leading UConn to a national title and being named Final Four MOP, but it was a grind to get there.

The fear of re-injury is real. According to Medvecky, there is a 20% risk of injuring the opposite knee, whether that comes from favoring the knee that was originally injured, moving differently out of fear or other reasons that have yet to be discovered through research.

Another UConn legend, Shea Ralph, had her career ended in 2002 after five separate ACL tears and surgeries made it impossible for her to return, even though she was drafted to play in the WNBA. Ralph, who is now the head coach at Vanderbilt, first tore her ACL in 1997 during an NCAA Tournament game. Her final injury took place in 2002.

Since then, several key advancements have been made. In addition to the mental side of ACL injury recovery being a priority, there are also ACL prevention programs across the country. The rehab process is also longer and more intense than it used to be. In the 90s, Medvecky says players were released from their rehab programs after six months. Now, those programs take a year, sometimes longer.

“Being released after six months wasn’t based on much science, simply because we didn’t have any to go on,” Medvecky says. “Nowadays, research shows that there is a serious risk of reinjury between six and 12 months because of strength deficits that haven’t been rebuilt.”

The surgery itself hasn’t changed much over the last 25 to 30 years, but if you go back even further, you can see just how far ACL recovery has come.

Trish Roberts on the USA Olympic team in 1976, a few years prior to her ACL injury.

When former Tennessee great, Trish Roberts*, tore her ACL in the 80s, surgeries weren’t done on the ACL itself. Medvecky says back then doctors focused on stabilization.

“They didn’t put a graft where the ACL lives,” Medvecky says. “They focused on things outside of the knee in order to try and stabilize the rotation of the unstable joint.”

When Roberts had surgery, a metal pin was inserted into her knee for stabilization. In 2019, when she had her knee replaced, Roberts asked the doctor if he would remove the pin and give it to her as a souvenir. But when she came out of surgery and asked for the pin, she was told that it had become so integral to the structure of her leg that “removal would cause irreparable damage.”

Roberts still has a massive scar thanks to what she refers to as the “train track stitches” put across her knee.

“They cut my knee completely open,” Roberts says. “But now, they don't even have to cut it open. Everything is done with a scope, which makes the recovery time much quicker.”

It’s been over 40 years since Roberts went through her surgery process. And in the next 40 years, more advancements will be made. According to Medvecky, research is always being conducted.

“Somebody has to go through trials,” Roberts said. “We were the ones that paved the way in terms of knee injuries. Now that they've done more research, things are a lot better. I’m happy to see things continue to advance.”

*For more on Tennessee’s Trish Roberts, the first black woman to play for Pat Summitt and first All-American in Lady Vol history, come back Thursday for a full profile!